Poliomyelitis is a potentially deadly and/or extremely debilitating disease caused by the poliovirus. Because of widespread vaccination since the introduction of polio vaccine in 1955, the United States has been polio-free since 1979 according to the CDC. Despite low poliovirus incidence in the U.S. and other developed countries, many developing countries still face the threat. There two types of polio vaccine that provide immunity for the virus–inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and oral polio vaccine. While both ultimately prevent the spread of polio, there are mitigating factors for each.

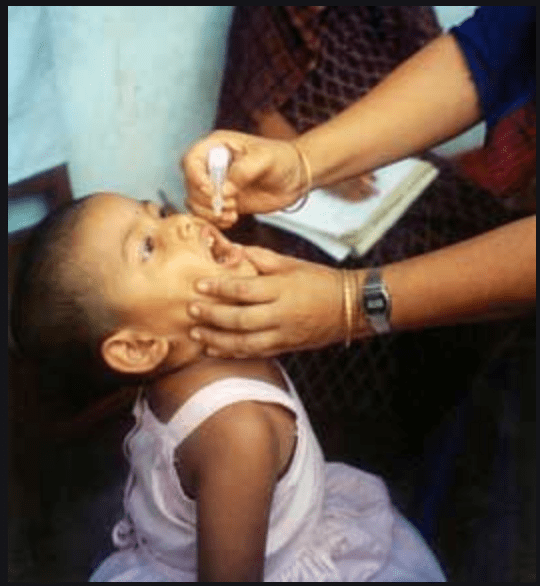

In the United States, IPV is the only vaccine series used for poliovirus since 2000. According to the CDC, children should receive four doses of the single-antigen vaccine at 2 months, 4 months, 6-18 months, and 4-6 years old. The vaccine is often contained in combination vaccines that lessen the amount of injections needed for children and infants, typically paired with DTAP, HepB, and or Hib. OPV, on the other hand, is used primarily in developing countries and is administered via droplets to the mouth. The Polio Global Eradication Initiative suggests that OPV is more efficient because it can be administered by volunteers. Additionally, they make the point that OPV has been declared Halal, which may be of consequence in many Muslim-majority countries still mitigating the poliovirus threat. OPV is also more cost-effective than IPV, making it more accessible for many developing countries. It is important to note though, that OPV requires several (even up to 10) doses to ensure immunity. Most concerning for me is that the exact number of doses needed is dependent on the child’s health and nutrition, creating a sort of guessing game that we may easily come out on the wrong side of.

Today, many in the U.S. think of polio as a thing of the past. Unfortunately though, according to Contagion Live, the 2018-2019 school year saw the number of children granted vaccine exemptions in public schools rise for the third consecutive year. This means that less and less children are getting the polio vaccine, and as world travel continues to become more prevalent, more opportunities arise for the poliovirus to strike again in the U.S. A response for this widespread vaccine-fear among parents has been combination vaccines. Contagion Live also reports new guidance from the CDC regarding a combination vaccine approved by the FDA in 2018 that protects against diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and polio. The vaccine will become commercially available in 2021 and hopefully encourage higher immunity numbers among children.

In a January article from Newswise, concerns are raised about both IPV and OPV in the scope of truly eradicating polio. Children given OPV can apparently shed mutant polioviruses that cause paralysis while the manufacture of IPV uses wild viruses that pose a biosecurity threat. The WHO has called for the invention and manufacturing of safer polio vaccines in response to the apparent dangers of our current methods. Initial efforts have been using gamma radiation to inactivate the Sabin virus for a potential vaccine. While these results were promising both scientifically and economically, more will of course need to be done by way of testing before this supposedly safer vaccine is commercially available. Ultimately, while the work on a new vaccine is certainly critical, none of these great scientific advancements in terms of polio or any other virus will be truly significant if the anti-vax movement grows. It is imperative that our governments, schools, and hospitals strongly advocate for and educate on the subject of vaccines for the health and wellness of any generations to come.